August 17, 2017

After our longish sojourn in mountainous terrain, we moved eastward onto the high plains with its far views across vast grasslands. Still in Montana, we tuck the trailer into a nondescript commercial park and immediately set off for Pompey's Pillar, an afternoon of rest and relaxation was but a fleeting thought.

Pompey's Pillar. . .

Although I had no earthly idea what Pompey's Pillar might be, the señor seemed to be anxious to view it and I am very glad he was. The natural rock formation might have been a little-noted landscape feature except for one thing: William Clark of the famed Lewis & Clark Corps of Discovery dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson encamped at the site and left irrefutable evidence of his presence by carving his name and date into the rock face, a fact he noted in his carefully-kept journal.

The formation rises 150 feet from the plain and is about an acre in size at its base - certainly a prominent feature on the bank of the Yellowstone River.

Before advancing to the pillar, now a National Monument, we perused the very interesting visitor's center, where we were steeped in additional facts about Clark and his companions as they made their way toward home in 1806 as the culmination of their three-year exploration to the Pacific.

At the time he saw and named the formation, Clark and Meriwether Lewis had temporarily parted ways in order to survey as much territory as possible. In Clark's contingent was the sole female of the expedition, Sacagawea, with her husband and child, Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, whom Clark affectionately called Pomp. He originally named the rock Pompy's Tower; it was altered in 1814 to its current title.

"At 4PM [I] arrived at the remarkable rock situated in an extensive bottom. This rock I ascended and from it's top had a most extensive view in every direction. This rock which I shall call Pompy's Tower is 200 feet high and 400 paces in secumpherance and only axcessible on one side which is from the N.E. the other parts of it being a perpendicular clift of lightish coloured gritty rock. The Indians have made 2 piles of stone on the top of this tower. The nativs have ingraved on the face of this rock the figures of animals &c."

Interestingly, after the death of their parents, Clark became guardian for Pompey and his younger sister.

Clark's engraved name and date are visible today - more than 200 years later, preserved now under a locked glass frame amidst many other markings made over millenia. It is believed that his engraving is probably the only extant on-site evidence of the entire expedition.

It seems that there are visitor centers and then there are visitor centers - some are a waste of space except for the convenience of restrooms, and some are wonderfully educational and informative about the particular site. The one at Pompey's Pillar was excellent, thus we were equipped with understanding as we walked out to the rock and up and up and up the very many steps that deposited us where Clark made his mark and then on to the top.

We learned about some of the tribulations the expedition experienced, one being the loss through theft of their horses, a staggering setback. Taking their cue from the local natives, they fashioned bull boats from bison hides and used dugout canoes tied together in pairs to continue on by river.

The view from atop the pillar stretched for many miles across the plains and allowed us to see the Yellowstone from yet another vantage point.

In addition to a fine interpretive center, the monument sits in the midst of a wonderful riverside grove of towering cottonwood and other trees, a brushy copse through which a trail winds. Of course we opted to return via that way instead of the civilized pavement and thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. We took heed of a warning sign and watched where we stepped; at the same time, we stepped fairly rapidly as the skeeters were gaining on us.

|

| We bade farewell to the Yellowstone, hopefully to return another time. It and many other waters we've seen in Montana seem to be welcoming to the casual kayaker fisherman. |

A back road, memories, old stuff . . .

Some map browsing and a little questioning to insure we would not be off on a wild goose chase allowed us to get to Pompey's Pillar via a little-used gravel road that turned here and there, first through open range land, then cornering around large dry-land wheat acreages and finally by green ditch-irrigated hay fields and the occasional small wandering stream.

I had to wonder just what life is like out here - surely the isolation is not as extreme as in the past due to modern transportation. Certainly everyone in the region knows everyone else despite long distances between homes; I imagine they socialize in relatively small circles and of course are on their own hunkered down during long winter storms. All in all, it was a pleasant though dusty drive; I felt drawn to the place in wanting to feel a part of it.

I saw one young man out to set up his afternoon irrigation run. It took me back into memory-land: he was doing his watering exactly the way we used to do it with our dirt ditches in Chino Valley. That was to lay one board horizontally across the ditch banks, then place several boards with one end stuck into the ditch bottom and propped at a slant against the top board. Next is to drape a tarp against the structure, poke the edges into the mud at the sides and bottom and adjust the top so that excess water can flow over into the next set-up. That backs up the water to a sufficient level that you can then start metal or plastic siphon tubes that get the water over the ditch bank and out onto the crop.

Never ones to pass by interesting old structures without at the very least a photograph and often a browse around, we've had plenty of opportunities for such in Montana. Indeed, we have encountered so many picturesque abandoned buildings that we have not stopped at them all. The vast distances required to get from here to there on the high plains might account for those omissions.

Chris wondered if this tattered structure on that back road was at one time a schoolhouse, a surmising brought on because of the bank of windows in the back.

This little falling-down homestead across from the supposed schoolhouse has been replaced by a nearby weather-tight structure and left to complete its return to the earth.

We couldn't help but be bemused by a scarecrow standing sentry at a teetering tiny adobe, the only earthen building we saw out there. They both seemed to be leaning at approximately the same angle.

Out there and in a number of places, we saw sandhill cranes plus a bird new for the trip: ring-neck pheasants - most often groups of juveniles. Other birds added to the trip list include western wood pewee, western kingbird and kestrel.

Little Bighorn Battlefield . . .

I wrote about the excellent visitor's center at Pompey's Pillar National Monument. The following day we were amazed at the interpretative center for the Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument. When all was said and done, we spent the best part of a day at that site, taking in most of what was offered.

A concessionaire offers battelfield tours conducted by Crow Indian guides; we were very grateful we started off with that (although curious about who was the Prescott couple there on an earlier tour). In their own language, the Crow are Absaalooke, meaning children of the large-beaked bird, learning English only as a second language, thus keeping their culture and language vital.

Our guide, Blaine, was a marvel of knowledge and passion about the events of and surrounding June 25 & 26, 1876, known as the Battle of Little Bighorn, sometimes called Custer's last stand.

I had not known what to expect at the site; as it turned out, my understanding of those momentous events was sorely lacking. Certainly I had no inkling of the scope of the battle field nor of the number of combatants.

I will leave it to anyone interested to do the research; my knowledge is far too limited to take on a dissertation of those two days during which many fell - warriors from both sides. It was illuminating to be on the site as Blaine pointed out the places of various incidents, and explained the intertwining groups and battles.

Following the guided tour, we watched a very informative film and then we walked much of the battleground, steeping ourselves in the place and reading interpretative signs placed along the way. Those were gripping in the way they told what occurred at each place and also included remembrance quotes from battle survivors or those who came upon the scene later - always one from a soldier and another from an Indian.

Looking down on the place where 2,000 or so tepees had been erected helped to visualize the encampments of so many combined tribespeople along the river. By all accounts, they had thought that combining their forces into such a huge group would insure they would not be attacked.

Looking across the opposite direction of the river, we could see whence the soldiers rode, many to their doom. Questions remain about Lt. Col. George Custer's intentions as he split his troops into three companies to engage the huge encampment which, at their approach came alive like a disturbed anthilll.

Two days of heated battle over a large swath of territory resulted in the deaths of Custer and his entire company as they made their last stand on a hilltop. As the gun smoke cleared and the din quieted somewhat, the Indians retreated in the face of General Terry's reinforcements nearing.

Survivors from the other two companies identified some of their fallen comrades by writing their names on a tiny parchment which they rolled up and inserted into spent cartridge shells to bury with the bodies. Most were not identified. In 1881, the bodies were reinterred in a central mass grave and stakes placed where they had fallen. Those stakes have been replaced by marble markers, anonymously for most, but named where they were known.

The mass grave is atop Last Stand Hill where Custer was also killed. He was later reburied at West Point and his officers at various places in the country.

It is sobering to look across the landscape, ridgetops and arroyos to see the monuments.

|

| Coins and stones have been left on some markers as a sign of respect and to denote that someone has visited. |

Desperation during the course of the battle had soldiers attempting to dig protective entrenchments with whatever was at hand: split canteens, spoons and so on. There are still traces of those trenches; examples of the implements are displayed in the museum.

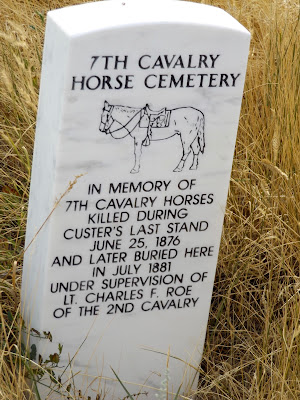

Because Custer's command was the 7th Cavalry, the soldiers were all mounted. As the battle became more and more heated, the men in desperation shot their surviving horses to use the bodies as cover, there being very little else at hand. Even their remains were assembled, buried and memorialized.

In 2003, an Indian memorial was erected at the site, a promise of peace among all peoples.

With those horrific events past, the scene now is one of tranquility.

. . . leads to another, at least in my world, thus a wondering about the purpose of a very large structure near Hardin led to a few other finds along the way. We had thought perhaps the building was a sugar beet processing plant after putting together two plus two. Large industrial building + road named Sugar Factory Road + sugar beet crops = nope, it was a power plant.

So that left us with a crop we had never seen before and a very defunct structure which must have been the sugar beet plant.

A little later research revealed that the sugar beet factory shut down in 1971, causing an extreme economic downturn in the area. We did not discern where the crops are now processed, but there are still large acreages of them being grown.

Okay, back to the one thing leading to another: Whilst skulking about on Sugar Beet Factory Road, I spied a nondescript sign about Arapooish Pond, so surely there must be water back there somewhere. That led us to wander yet another dirt road that was not marked and looked for all the world as if it was someone's driveway. Oh well, we might have to apologize and turn around in a private yard but we soldiered on because after all, a pond must be somewhere around there.

Along the way, I spotted an awesome hornet's nest, a marvel of insect industry; luckily, it was way high in a tree where we would not be likely to encounter those horrid little beasts.

We were a bit surprised when at the end of the lane, we came upon a lovely large pond (in Arizona, it would be called a lake) with not another person in sight. We hiked around most of its perimeter, stopping when the brush on the far side became much too thick to allow watching for rattlesnakes. One garter snake slithered quickly across my path to disappear into the grass. We spooked out numerous ducks from an adjoining reed-choked waterway and watched kingfishers dive repeatedly into the water for their supper.

Further exploration brought us to the Bighorn River from which Arapooish is fed; we hadn't realized we were that close to the river. We were a little surprised to see so many pigeons (rock doves, in birder parlance) around that region. They were feeding in the harvested wheat fields and perching in pairs on the river's cliffs.

Smoke, Bighorn Canyon NRA

We were in Hardin for only three days, although our activities during that time made it seem much longer. A place called Bighorn Canyon National Recreation Area sparked some curiosity, so we drove out to see what it was about.

Traveling through ranchland took us by several settlements of a sort, mostly abandoned. Little remains of the town of St. Xavier, but the ruin of what was an impossibility large brick school was quite unexpected. Where had all those students come from and where had they gone?

An old wooden structure was tucked up against the side of the defunct schoolhouse; we thought it was possibly the precursor to its neighbor.

The sights along the drive out to the Bighorn NRA revealed mostly crops of sugar beets, wheat and alfalfa with a couple of sunflower fields thrown in for good measure.

In addition, there were numerous fishing accesses, resorts, cabins and rentals. Fishing on the Bighorn through that region is said to be excellent.

Winding a ways up through the hills revealed interesting and pretty countryside opening up to a stupendous canyon. That was the good news. The bad news was that there is no, repeat no place to hike or drive. It is strictly a marine-type recreation area, although it looked wonderful for boating and fishing and was not at all overly busy. Perhaps a return is in order for a time when we have Montana fishing licenses.

Red cliffs that were stunning when we drove up the mountain were nearly obscured after the short time we were there. Wildfire smoke rolled in very quickly and soon overwhelmed the landscape.

Crow fair . . .

The town of Hardin borders the huge Crow Indian reservation. By happenstance, the annual Crow powwow was scheduled for the weekend that we departed that area. Naturally with the proximity of town and reservation, there are many Indians around. Those numbers increased dramatically with the influx of powwow attendees - traditionally, thousands of folks arrive for what seems like a gigantic reunion, games and activities. An estimated 2,000 tepees are erected at the site, coincidentally the same approximate number in the encampment attacked by the 7th Cavalry in 1876.

We drove through the grounds where I hoped to get some good photos; however, the congestion, tight quarters, pedestrians and riders made it more than difficult. It also felt very intrusive, so we gave it up.

It was interesting to see the cottonwood-branch-covered arbors that were erected and that so many of the campers brought their horses. Indeed, lots of folks were riding throughout the encampment and the area, all bareback and all clearly experienced riders. The photos do not convey the scope and general chaos of the powwow area, unfortunately.

2 comments:

I just love your blog! Feels like I've been there and envy that you and Chris actually were!

Moving to San Diego area in the next month. Don't know if I'll run into you guys again but will always read and appreciate your words and photos.

Terri

Terri, I am so sorry to hear that you are moving away! I will miss seeing you, but remember, it's not that far - you can come back to visit. And San Diego is wonderful, plenty of English country dance over there and I hear tell there's an ocean, too, quite a nice feature. Please stay in touch. I wish you well.

Post a Comment